Agnes Pelton

1881-1961

Agnes Pelton was a pioneering American modernist whose nature- based abstractions, begun in the mid -1920s, established a new direction for progressive painting in this country. Pelton’s works were poetic celebrations of nature that explored the vital forces animating the physical world.

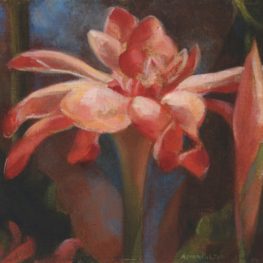

Interested in themes of creation, growth, and radiance, Pelton translated favorite subjects — a glowing star, an opening flower — into life-affirming images of rare beauty and resonance. In many ways, her paintings resemble the art of her contemporary Georgia O’Keeffe, only more colorful, more spiritual, and more imaginative.

Pelton led a fascinating, bohemian life. Born in 1881 to American parents in Stuttgart, Germany, she was raised in Brooklyn, New York. The granddaughter of Theodore Tilton, a leader in America’s abolitionist movement, Pelton supported idealist principles throughout her life. Her father, William Halsey Pelton, was the idle son of a wealthy Louisiana plantation owner. He lived a dissolute life: ignoring family obligations, traveling through Europe. A manic-depressive, he died of a morphine overdose when Agnes was nine.

Her mother, Florence Tilton, was studying music at Stuttgart Conservatory when Agnes was born. After her husband’s death, Florence returned to her family home of Brooklyn and opened the Pelton School of Music, a piano school she operated for the next thirty years.

Her father’s early demise left Pelton a melancholy, introverted young girl. In 1895, at the age of fourteen, she enrolled in the general art course at Pratt Institute. She had the good fortune to study with Arthur Wesley Dow, an important figure in American art education, probably best known for instructing Georgia O’Keeffe. Pelton graduated in 1900 with classmate Max Weber, another early American modernist.

During the 1910s, Pelton located her studios at the center of radical politics and avant-garde art, Greenwich Village. She began to produce her first independent works: a series of symbolist figure compositions in pastoral settings that she called her “Imaginative” paintings. Pelton wrote they represented “moods of nature symbolically expressed.” Inspired by the art of Arthur B. Davies, these charming images recalled the British Romantic poets and turn-of-the-century European aestheticism. Two were included in the landmark Armory Show of 1913.

Pelton’s life and art changed radically with her mother’s death in 1921. She turned her back on Manhattan and relocated to a historic windmill near Southampton, Long Island. Pelton’s life became a quest for peace and solitude. She was enchanted by the seclusion of her quaint windmill home: a “mystical house, reaching into heaven and radiating from its center, distributing sustenance.” In this spiritual environment the artist turned inward and began to paint abstractions based on natural phenomena in 1926.

The last chapter of Pelton’s life began in 1932, when the windmill was sold by its owner. At the age of fifty, Pelton traveled cross-country and settled in Cathedral City, a small town adjacent to Palm Springs, California. She originally planned a short stay, but, taken by the region’s stark beauty, she remained for the last thirty years of her life. Pelton explained, “The vibration of this light, the spaciousness of these skies enthralled me. I knew there was a spirit in nature as in everything else, but here in the desert it was an especially bright spirit.” Her California abstractions captured the region’s glowing light and vibrant aura.

The artist’s life in California was largely uneventful; she rarely left the desert. Though a group of young modernists worked in Los Angeles during the 1930s, she did not associate with them. But in 1938, she helped found the Transcendental Painting Group, an association of New Mexico artists committed to spiritual abstraction.

Raymond Johnson, their leader, invited Pelton to act as the group’s first president, though she was the only member who did not reside in New Mexico. Pelton was ten years Johnson’s senior, and twenty to thirty years older than the others. They looked to her as a role model. In particular, they admired her ability to pursue an independent artistic vision, far removed from any major art community.

Ironically, Pelton’s art, although little-known today, was acknowledged and acclaimed during her lifetime. Besides participating in the Armory Show, she exhibited in various New York galleries, such as McBeth and Knoedler, in the 1910s and 1920s. Pelton was honored, during the 1930s and 1940s, with one-person exhibitions at all of California’s major art museums, including the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Santa Barbara Museum of Art, the Laguna Art Museum, and the San Diego Museum of Art. Unfortunately, interest in her work declined after World War II. Pelton had no family, and did not possess the energy or charisma to actively promote herself. She died a neglected figure in 1961, at the age of eighty.

Biography courtesy Michael Zakian