John Storrs

1885 – 1956

John Storrs is perhaps best known for his columnar, architecture-inspired sculpture made of metal and stone of the early 1920s. Yet Storrs created masterful works in many other media throughout a career spanning nearly fifty years and two continents. He began his artistic training in the United States before moving to Paris in 1911. There he formed not only artistic but also personal alliances. While in Paris, Storrs developed an early friendship with Jacques Lipchitz whom he met in art school; met and married a French writer, Marguerite De Ville Chabrol in 1914; and studied and worked with the sculptor, Auguste Rodin, with whom he remained close until the master’s death, in 1917. His work of the teens included not just sculpture but also woodblock prints. The cross-fertilization between works in these two complementary forms of expression– carving from a block to make a three-dimensional object in space, and carving from a block to make a print–led to breakthroughs for Storrs in both media.

A group of his woodcuts focused on Walt Whitman (along with another entitled, War, in so far as it uses fairly conventional symbolic or allegorical imagery) represents one aspect of Storrs’ engagement with the modern revival of the woodcut – that of the print as book illustration. The great majority of his woodcuts, however, demonstrate his involvement in a much more significant aspect of the revival – that of the woodcut as a reflection of the modernist rhetoric of primitivism. Attractive for the directness and simplicity of its technique, the woodcut also conveyed an archaic, anti-classical sensibility. It was the ideal graphic medium for modernists who felt that academic conventions were antithetical to truth and authenticity. Storrs, employing an abstract formal language rooted in avant-garde circles of post-impressionism, symbolism, and to a lesser extent, expressionism, was an active agent in this widespread dialogue among printmakers in both Europe and the United States.

His first one-artist show at Folsom Galleries in New York in December of 1920 presented these prints and early sculptural works with equal emphasis. Among the sculpture included in this exhibition, which also traveled to the Arts Club of Chicago, were Rodinesque pieces, examples of war themes as well as newer sculptures in which he expressed aspects of modern life, often working with two and three figure compositions. Storrs left out of the Folsom Galleries exhibition the advanced non-objective sculpture he had produced from about 1917-1919—terra cotta and stone pieces in which no reference to human or animal form was evident. During this period, Storrs experimented with small painted terra cottas, inlaid stone relief panels, and inlaid sculpture in the round. The terra cottas of this period reflected the combined influences of Cubism, Futurism, and especially, Vorticism; although he gradually moved towards complete abstraction. One of these terra cotta sculptures, Untitled (The Dancer), ca.1918, was purchased by Katherine Dreier and bequeathed by her to the collection of the Société Anonyme, now at the Yale University Art Gallery.

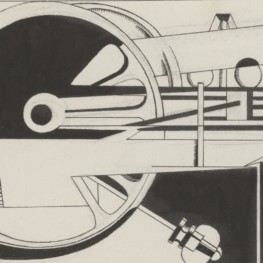

In the 1920s, Storrs developed an aesthetic based on the stylization of Art Deco, using sleek metal forms that suggested skyscrapers and evoked the urban landscape. His work was included in exhibitions in Europe and America, including several organized by the Société Anonyme in New York. A 1923 one-artist exhibition at the Société Anonyme in New York, which also traveled to the Arts Club of Chicago, established Storrs as a member of the international avant- garde. Included in this exhibition were drawings along with twenty-one sculptures, and those executed after 1920 show Storrs moving more and more in the direction of architectonic sculpture. His more architectonic works, such as Untitled of ca. 1922 have been compared to the work of Jacques Lipchitz. Noted Storrs scholar Noel Frackman compares this work to Lipchitz’s Man with Mandolin, 1916-17, with its basis in figuration while architectural elements are equally evident through blocky, tower-like forms. Storrs continued to embrace modernist ideas and themes throughout the decade of the twenties. His Auto Tower marks the artist’s continued interest in the machine, a taste shared with Francis Picabia, Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray, Morton Schamberg, and others connected with Dada, Surrealism, and the Société Anonyme.

Storrs’ career began to flourish, and as the decade of the twenties drew to a close, he had received several commissions for monumental outdoor projects. One of his most recognizable sculptures created during this period, Ceres, sits atop the Chicago Board of Trade Building. Storrs also received a contract to design a number of elements for the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair. His freestanding statue, Knowledge Combating Ignorance, with its position at the end of the Avenue of Flags, the main entrance to A Century of Progress, was the dominating sculpture of the Fair. As with each of the previous decades, the 1930s saw a new flowering of Storrs’ artistic endeavors. In 1930, at the age of forty-five, John Storrs began painting seriously while still continuing his sculpture projects. His daughter, Monique Storrs Booz, often said that her father began painting while waiting for the committee of A Century of Progress to make up its mind.

Storrs exhibited his paintings for the first time in Chicago in 1931 at the Chester H. Johnson Gallery. His earliest paintings employ the same complex abstract forms present in his sculpture. It is possible that some of the impetus for pursuing painting came from his friendship with other artists, specifically Marsden Hartley, with whom Storrs frequented galleries. Storrs also knew Fernand Léger; and the hard-edged machine like aesthetic is common in both artist’s work of the 1930s. By 1938, John Storrs had received public recognition –being made a Chevalier of the French Legion of Honor–and the admiration of his peers in the art world. In 1939, at the outbreak of World War II, the Storrs family had just returned to France from a trip to America. Unbeknownst to Storrs at the time, he would never again return to America. He was arrested and imprisoned for six months in a concentration camp (Front-Stalag 122, Compiègne) in December of 1941. Storrs was an artist whose acute visual sensitivity made the sights that surrounded him in Stalag 122 unbearable. A series of beautifully expressive silverpoint drawings of his fellow inmates at the concentration camp done in the forties illustrates the profound and lingering impact that the war would have on him for the rest of his life. Later paintings by Storrs created in the years directly following World War II are more painterly, representational compositions featuring Chantecaille, the chateau and grounds he shared with his wife in France. Psychologically drained by the war, Storrs’ paintings from the 1950’s are highly symbolic, tonal paintings with one or two figures dwarfed by the landscape.