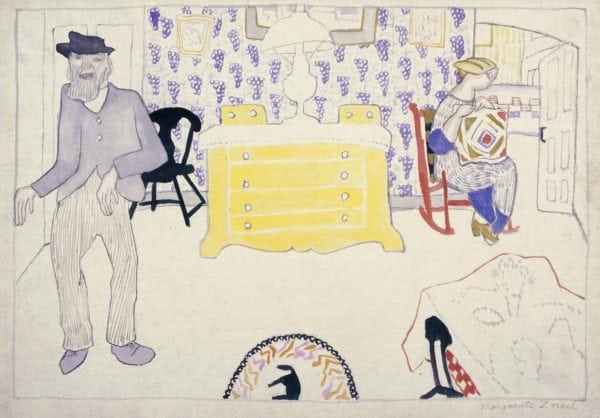

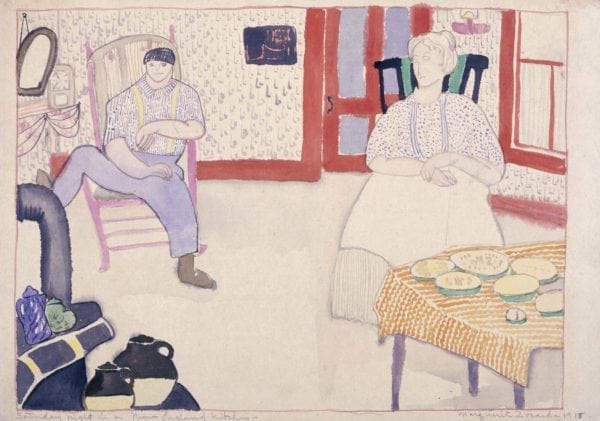

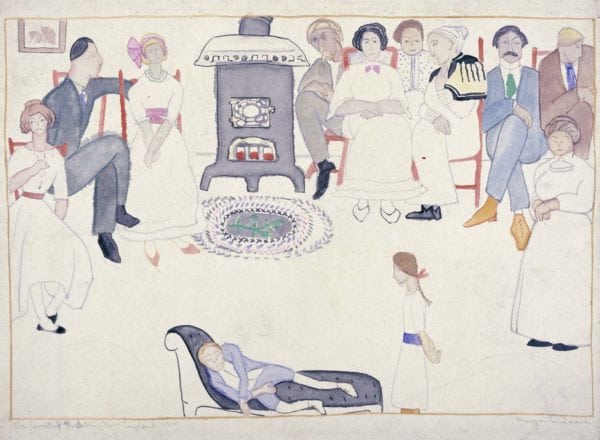

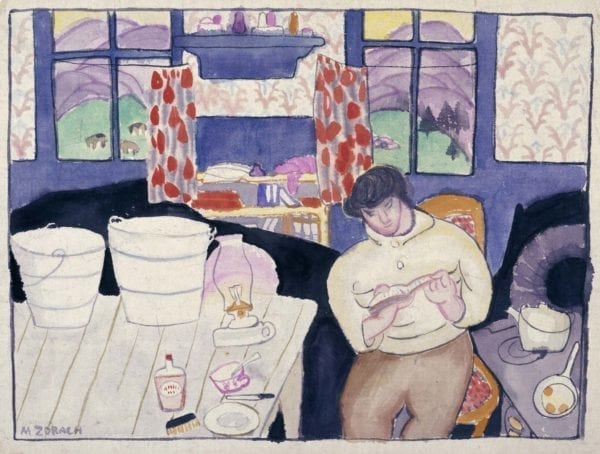

5 Works from MoMA, 1915

Marguerite ZorachWatercolor on paper mounted to board

11 × 16 inches

Signed lower right: Marguerite Zorach

Provenance

Marguerite Thompson Zorach, New York, NY

The Downtown Gallery, New York, NY

Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, New York, NY

Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY

This work is part of a group of six original watercolors created during a summer excursion in 1915 to the White Mountains hamlet of Randolph, New Hampshire. Zorach also turned five of the six original watercolors into a set of hand water colored transfer lithographs.

This set reflects life in the White Mountains hamlet of Randolph. A noticeable feature in these works is the attention to detail, everything from the furniture in the rooms to the patterning of the wallpaper and the design of the rugs. [Marguerite Thompson Zorach] emphasized the shapes of the objects by juxtaposing them against a dark ground. This can especially be seen in Interior, White Mountains* with the rhythmic play of the gray pails, the orange glow of the lantern, and the light blue stovepipe that contrast with the near-black area behind them. In general the work displays the modernist conventions of simplification of form and dramatic flattening of perspective, which is especially evident with the plunging tops of the stove and table. This work and others in this early lithographic series are unusual in Marguerite’s graphic oeuvre for their color. Even later, when she was associated with the Provincetown Printers, the printmaking organization that helped popularize single-block multicolored prints, Marguerite stuck with black-and-white linocuts.

Not only do these works reveal Marguerite’s interest in lithography, but each piece reads like a page from a visual diary. In Interior, White Mountains, a figure (either Marguerite or William) sits in a orange chair between the stove and dining table. Breakfast preparations are underway as the yellow light of dawn breaks over the hills and through the two windows. A pot is boiling on the stove and eggs are frying in the pan. The table is set for one. With the lantern and water pails, it appears there is no electricity or running water. One senses the difficulty of the figure in trying to balance domesticity with the pleasures of reading a book, or in the case of the Zorachs, making art. In this frank portrayal, the balance between the artist and the generally perceived traditional role of the woman as homekeeper is evident. William [Zorach] alluded to a similar struggle in “The Home (New England),” a poem from 1915, written when they were in Randolph:

The house was full of things rooms full of things

The kitchen was full of people fussing with food—

clattering dishes

The house was heavy with suppressed words—The incessant vibrations of the child jarred in every nerve

No one had time to step outside the door— Yet outside the house were still trees

and wide meadows

and silent hills

And children and dogs and flieswere happy things

There was joy in the sun-hot violetsand in the new red buds—

and peace in the vibrating air— Yet no one stepped outside the door—